Confused Deputy Problem – How to Hack Cloud Integrations

Write-up on techniques to exploit cloud integrations in SaaS platforms.

Intro

Some SaaS “AWS integrations” are only one AssumeRole away from becoming a cross-tenant data access problem.

Not because AWS is broken, but because the SaaS integration layer often fails to bind tenant identity to cloud identity in a way that holds up under real attacker behavior (guessing, reusing values, finding legacy trust paths, and abusing configuration surfaces).

This post is a practical write-up of confused deputy patterns I repeatedly observed while assessing cloud integrations.

Confused Deputy Problem

What is the confused deputy problem?

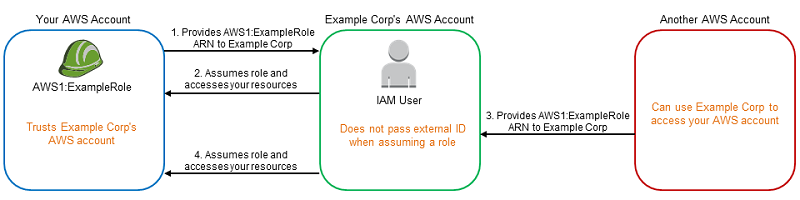

A security vulnerability where a trusted, higher-privileged entity (the "deputy") is tricked by a less-privileged entity into misusing its authority to perform actions it shouldn't, leading to unauthorized access or privilege escalation.

In this context, the deputy is the trusted SaaS platform that offers cloud integrations (AWS, GCP, Azure). for example S3 import/export, CloudTrail ingestion, or cloud cost analytics.

Therefore the SaaS company may have broad access to customer AWS accounts, and it is their responsibility to secure that access.

Link to AWS Confused Deputy Documentation

AWS Role Assumption

There are several ways to integrate an AWS account into a SaaS platform (cross-account access):

- Static AWS access keys (still common, and sometimes the only option)

- IAM role assumption

- OIDC

This write-up focuses on IAM role assumption, which allows cross-account access without hardcoded credentials.

From AWS Documentation:

But how does it work in real life?

- SaaS company has a custom IAM Role (or IAM User) in their AWS account with an IAM policy that allows to assume any role.

- Customer creates a role in their own AWS account with a trust policy that trusts SaaS company's AWS account for role assumption with the necessary permissions to access resources.

- When the setup is complete, the SaaS company's service try to assume the role in customer's account and if succeed, the service will have the same permissions as the IAM role in customers account

This seems straightforward. To make it secure, AWS introduced a conditional parameter that must be provided during role assumption from the SaaS service. This is called ExternalId. The idea is that every customer has their own ExternalId value tied to their account within the SaaS platform and included in the IAM role's trust policy. If another customer tries to add the same AWS IAM role for integration, it would have a different ExternalId, so it would not work.

This is an ideal scenario, but let me get back to this part later.

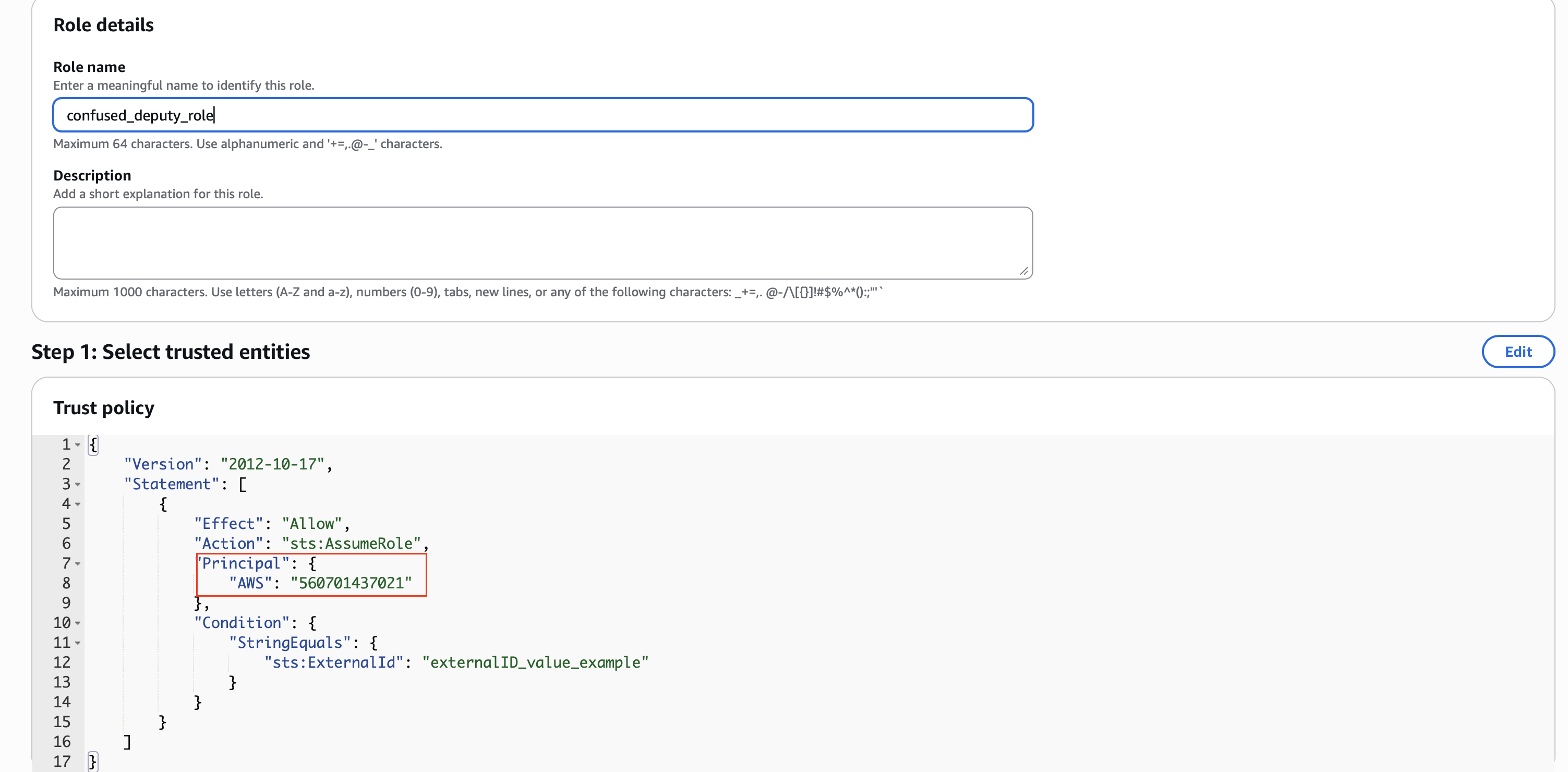

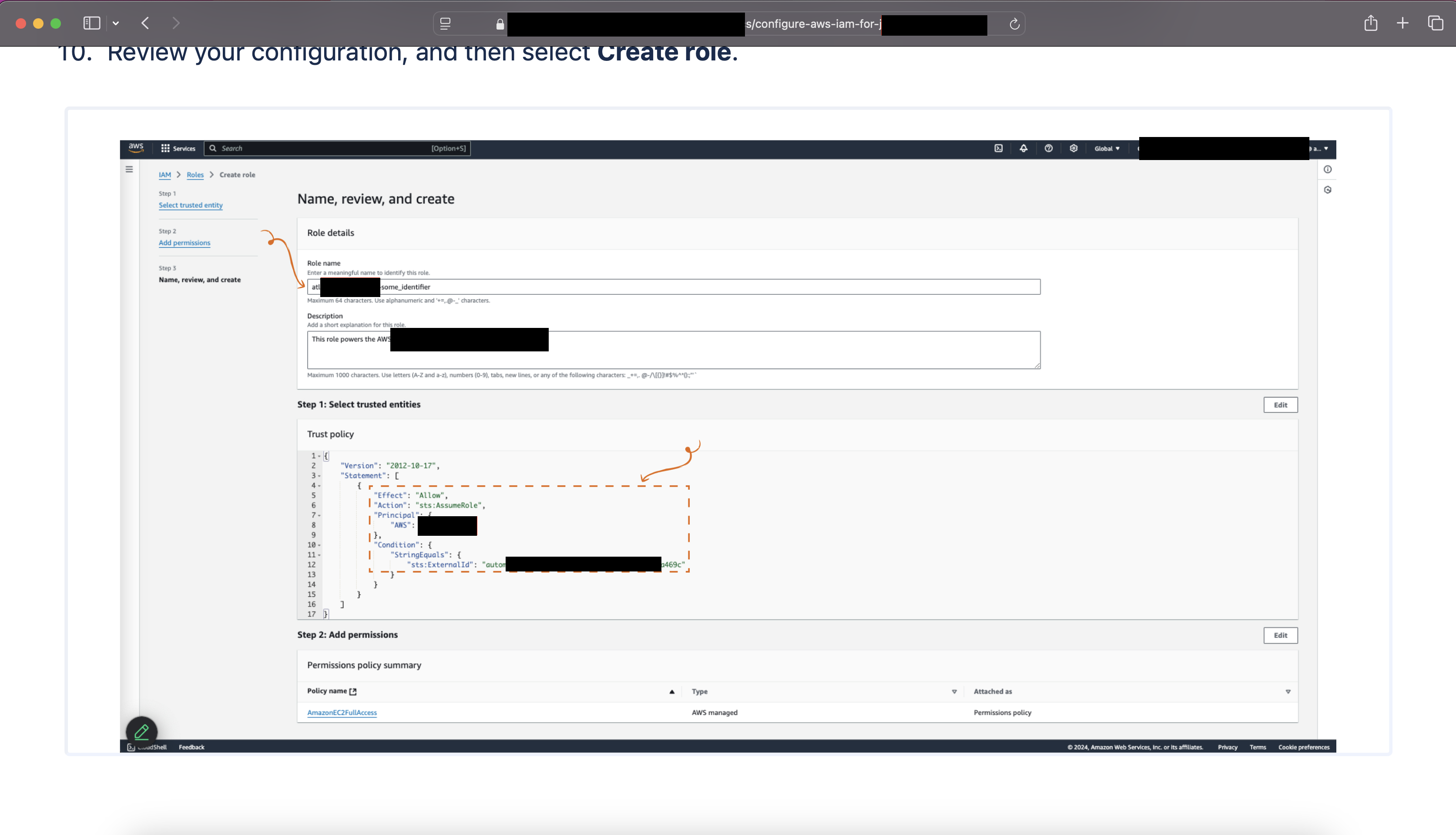

Below is an example trust policy that grants access to AssumeRole from any user/role in AWS account 560701437021 if the ExternalId value is present:

How it started?

I was working on an analytics SaaS platform and had already reported issues (including SSRF to AWS metadata, which gave me information about the company's infrastructure and naming conventions). I noticed they had an S3 import integration that used IAM role assumption.

I read the documentation and realized that cross-account role assumption with ExternalId seems secure, so there was no obvious path to accessing other customers' data. But I had an idea: what if I tried to access internal resources instead? Everyone trusts the AWS implementation, but has anyone ever checked what happens if the S3 import tries to assume an internal role?

Well if everybody would have included this into their threat model, then this write-up would not exist.

I tried a few role names using an AWS IAM role enumerator and found a default Readonly role that existed in that account. That gave me access to every production S3 bucket, and I could import the contents via a custom parser to my account.

This was the moment that got me thinking, if there is this issue and nobody found it, there must be others. I searched and collected all the available bug bounty targets that have cloud connectors/integrations and started looking into the implementation one by one.

That OrganizationAccountAccessRole

The first big bounty

As I was digging deeper and deeper into AWS IAM documentations I had different ideas that I wanted to test and constantly learned new things after already looking at 10-20 integrations in different programs.

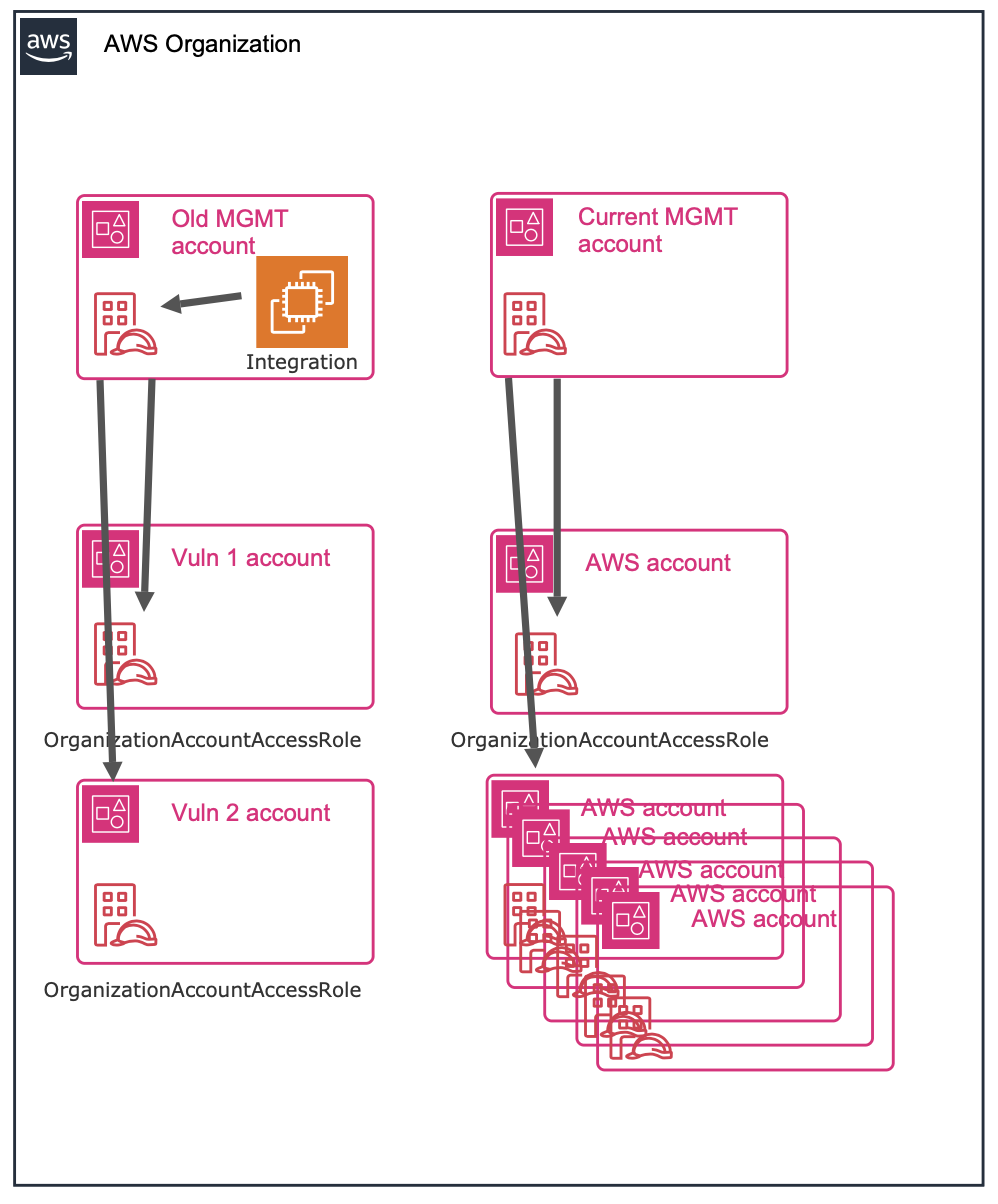

One role that consistently came up was OrganizationAccountAccessRole found by my role enumerator in most AWS accounts. But what is it?

From AWS Documentation:

By default, if you create a member account as part of your organization, AWS automatically creates a role in the account that grants administrator permissions to IAM users in the management account who can assume the role. By default, that role is named OrganizationAccountAccessRole.

So this means that if it exists, the AWS account belongs to an AWS organization and from the management account it is possible to assume that role with administrator privileges.

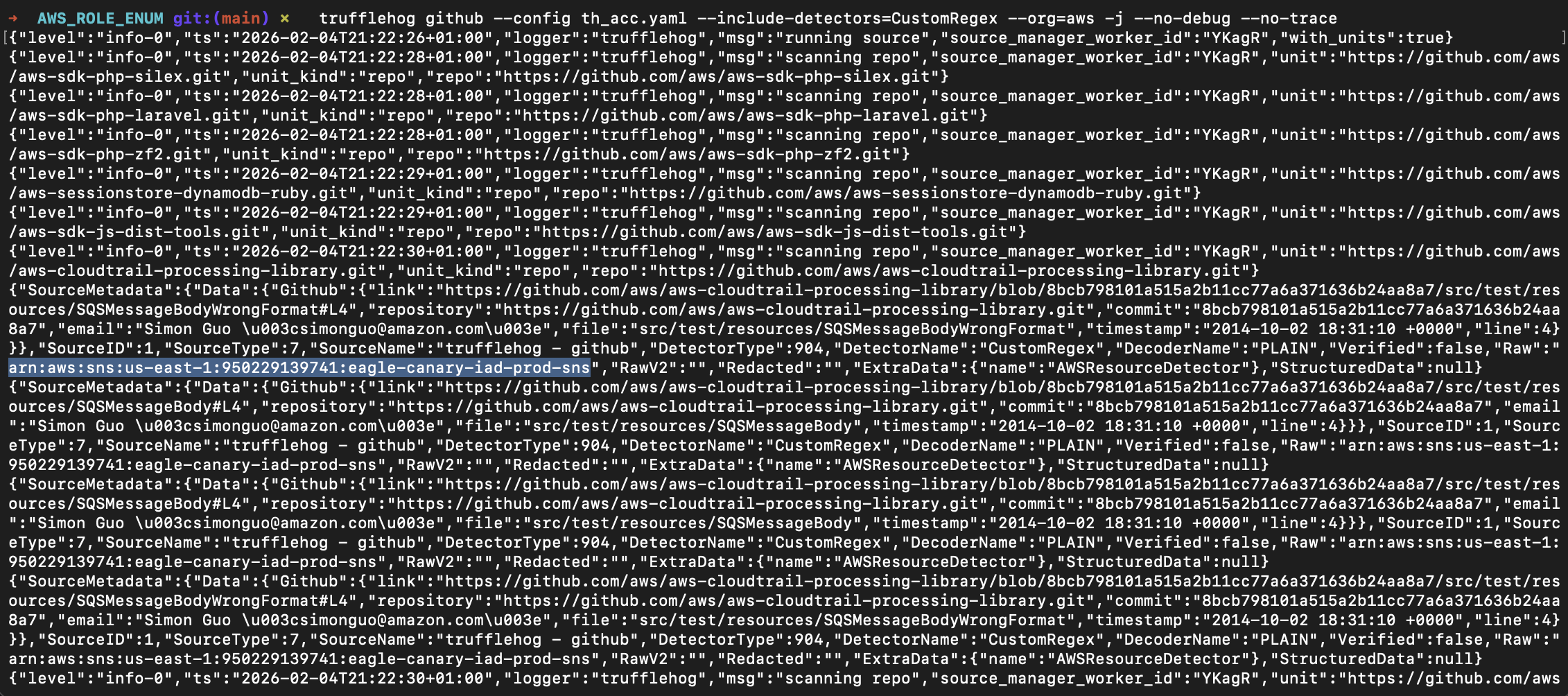

One of my target had an AWS integration, and I collected different AWS account IDs from CloudFormation templates used to deploy their integrations. I started scanning for existing roles and, as expected, found OrganizationAccountAccessRole in most accounts, but it didn't work for most, until one account's OrganizationAccountAccessRole was accepted. Within minutes, that account's resources were populated into my account. I was surprised, and then tried to find more AWS organization IDs. I created a modified Trufflehog template to find AWS resources and extracted account IDs from their GitHub organization. Surprisingly, it worked and I managed to gather a few more accounts where OrganizationAccountAccessRole was present and assumable by the integration.

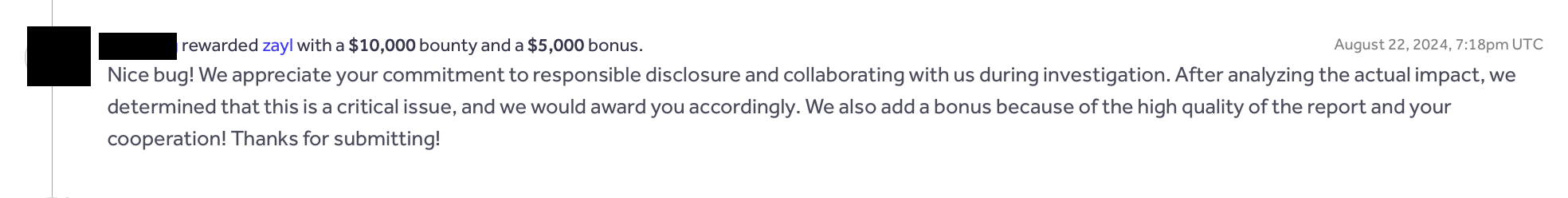

By the end of the night I had onboarded 3–5 different AWS accounts to my SaaS platform and could access S3, EC2, Lambda, RDS, DynamoDB, and more. I quickly reported it to the company, and soon received the maximum payout:

How could this happen? I suspect the account where the connector service was deployed might have been an old management account. The other accounts were part of that organization, and the roles were not cleaned up after restructuring. Therefore the trust policy still allowed any role from that account to assume the role with administrator privileges.

Another OrganizationAccountAccessRole issue

I was testing another platform's cloud integration and obtained their test AWS account ID. I found that OrganizationAccountAccessRole existed in that account but not in the one where the integration service runs. I quickly created a connector and within minutes had administrator privileges in their test account. Because the integration was pipeline‑like, I could run any AWS CLI command.

Thank God we have ExternalId so we are secure (or not)

I found many integrations where I did not managed to harvest too much information about the company's cloud infrastructure nor other AWS accounts, so I decided to play around with the integrations and see if I can abuse it somehow.

When ExternalId can be changed

The whole idea of ExternalId is that it is part of the IAM trust policy, so role assumption, even from a trusted account—is not possible without the ExternalId value. When I test an AWS integration, my first test case is: can I change the ExternalId value? If so, that is a classic confused deputy problem, although most companies won’t treat it as an issue without a proof of concept.

The integration allowed arbitrary ExternalId value

A large company’s automation integration allowed specifying the RoleArn and ExternalId value, which was a red flag. But if I reported it as‑is, it would need a lot of clarification and at most be medium severity. So I dug into their documentation and YouTube tutorials. I found the company had used real values in the docs without redaction or cleanup.

A highly redacted (by me) screenshot of the original documentation website, where everything was visible - Role Name, ExternalId value, Account Id

I entered the values from the documentation and managed to add multiple roles successfully. At that stage I submitted the issue, knowing I had a working POC. I never expected it to be a P1 with the maximum payout.

After that, I still tried to collect as much information as I could (AWS account IDs and role names) and add more to the integration, but once the original issue, changing ExternalId was fixed, I didn’t have much hope.

One time I asked ChatGPT to generate a list of role names based on my collected patterns. To my surprise, it produced a role name that existed in one of the accounts. Because it was not properly set up (no ExternalId), I was able to add that account too, which led to another P1.

If a role does not have ExternalId configured in the trust policy, you can still assume it even if you supply an ExternalId value. Furthermore, when testing blindly whether you can modify ExternalId, it’s a good idea to try 1–3 characters, because the role assumption will fail differently and might give you a hint from the error message. (Minimum length is 3.)

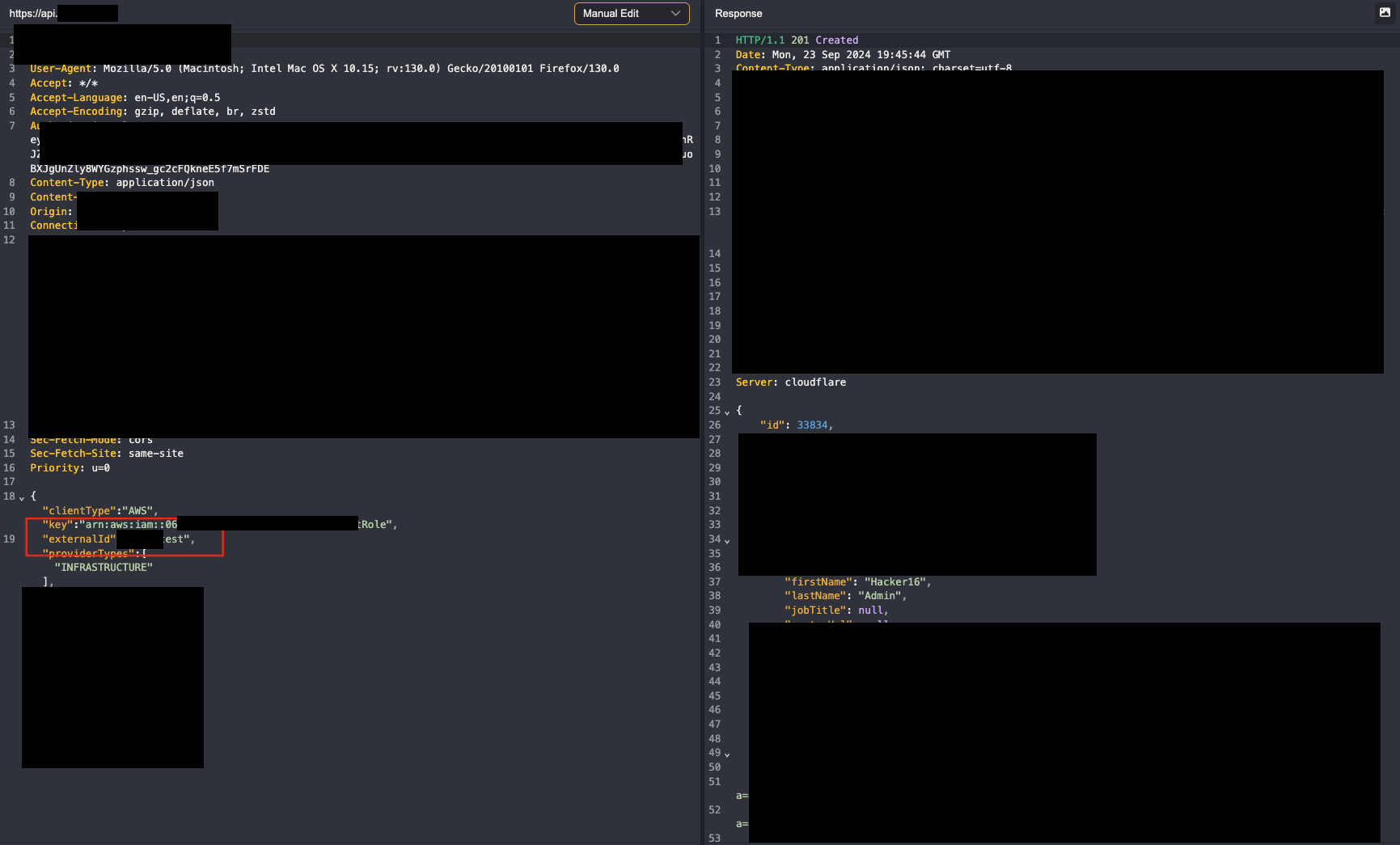

Modifying the request body to add arbitrary ExternalId value

A compliance tooling company had many integrations, including AWS. The setup was limited: it only accepted a role ARN if the role name matched their product name. The role name was always the same (CompanyRole), and the ExternalId value was the tenant ID. Even though the options were limited, I still looked to see if I could find something.

When I saved the integration, The request with the JSON object did not contain the ExternalId value; however, I could see from the response that it was part of the saved attributes. By simply adding it to the original POST request, I managed to set an arbitrary value. Great! At this stage it was another confused deputy, so I needed a POC to increase the severity.

While scanning for their own production AWS account ID (where they also run the integration), I noticed they used their own product. That meant I just needed to figure out their tenant UUID so I could set the right ExternalId.

This tool exposes a security page to customers, so I visited the company’s own security page and checked whether any API calls exposed the UUID. Luckily, all the assets were saved in their S3 bucket under the company’s ID path:

Putting everything together allowed me to onboard the company’s own production AWS account to my account and view all resources from a compliance perspective.

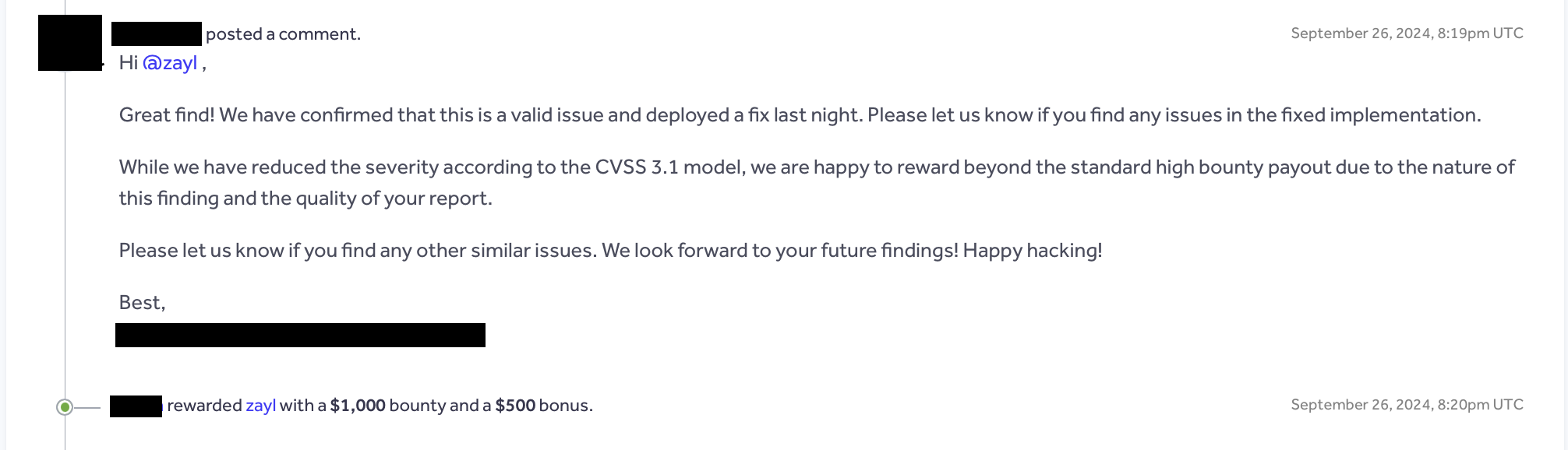

This was rated as High and rewarded with a bonus:

Issues where I could not provide a POC

There were many cases where I could modify ExternalId to an arbitrary value, but I couldn’t find a lead to add a leaked customer or the company’s own integration. This still means it’s a confused deputy issue, so to get it accepted I had to find the best way to demonstrate the attack. Usually I set up the integration properly in my own account and provided it to the triagers to add to their account with only the Role ARN and ExternalId value. In my experience, these values are rarely treated as secrets. Therefore anyone who has or once had access to this information (current/former employee) can set up the integration in parallel and stay unnoticed while gaining access to the company’s AWS infrastructure.

So with a proper POC and reasoning 4 out of 5 times it was triaged and accepted by the companies.

Confused Deputy with Export functions

AWS S3 Export

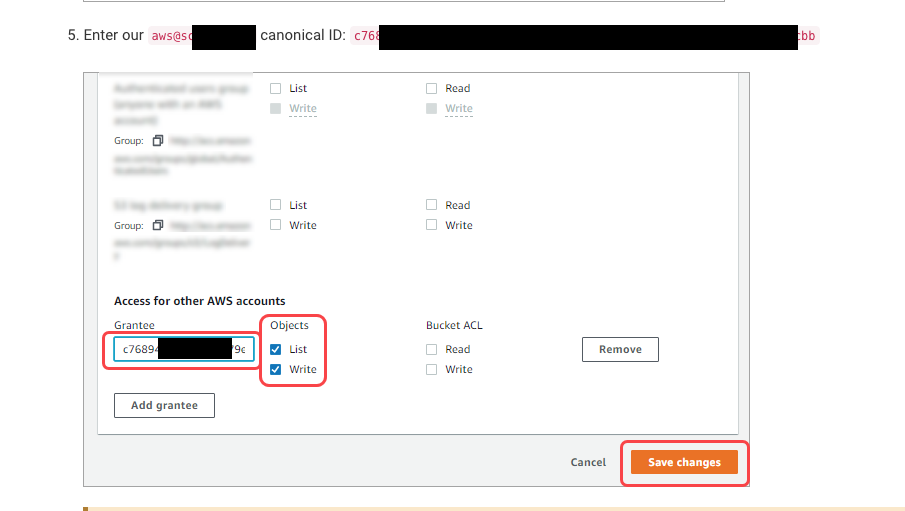

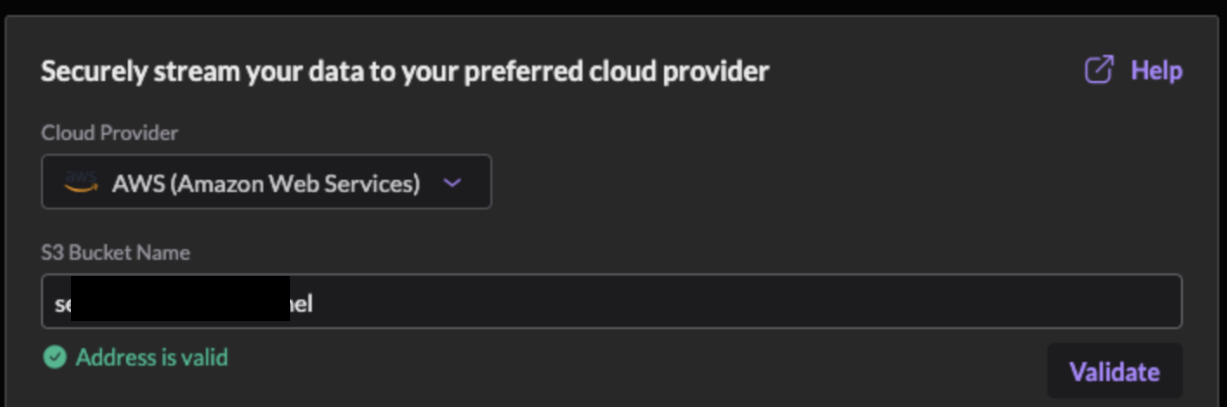

One security solution company offers data streaming (logs, etc.) to various destinations (S3, GCS, Azure Blob), and I noticed that the setup only requires entering a bucket name. After reading the documentation, I realized customers must modify the S3 bucket ACL and grant access to another AWS account’s Canonical ID (a long string that identifies an AWS account).

This means every customer for this setup trusts the same AWS account for their S3 bucket. In the case of S3 ACLs there is no ExternalId or similar control, which means that with only the bucket name you can add other customers’ S3 buckets as a destination.

Based on the company name and the function, I managed to find a few valid bucket names and validate them in the platform.

Tools and methods

Parallel Enumeration

I mentioned many times that I enumerated available roles in the company's account, but how does that actually work?

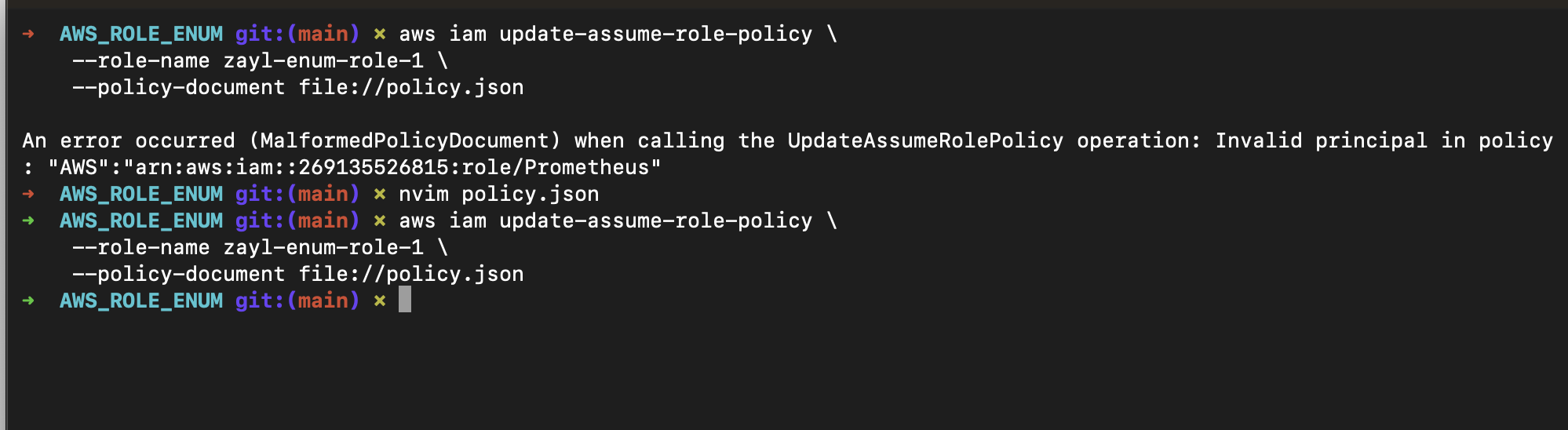

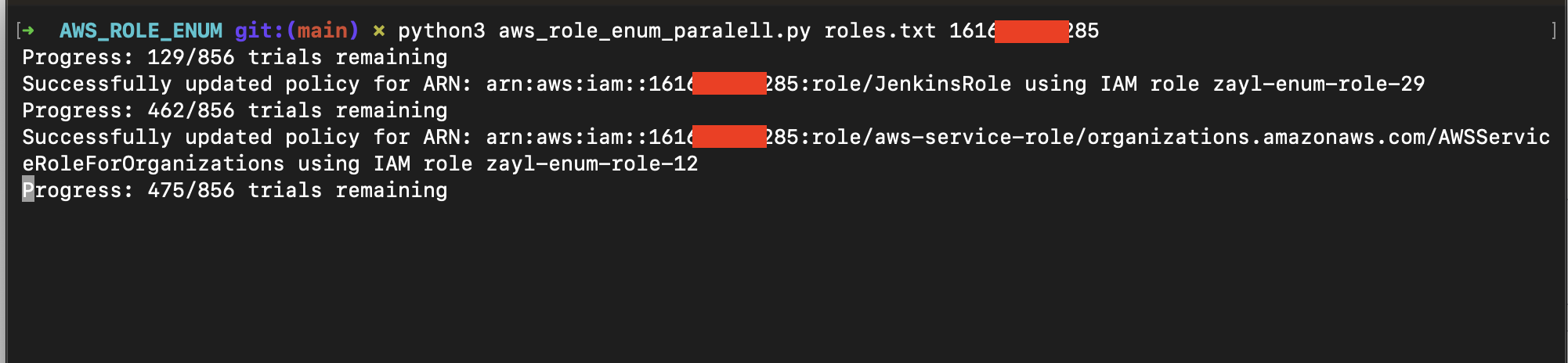

The technique is a bit old, but it relies on AWS behavior: when you set up a role trust policy and provide a Role ARN, it must exist. Otherwise you can’t grant access and you get an error. This technique never generates any CloudTrail log in the target account, so you can safely check whether a role exists.

I created 50–100 roles in my AWS account and, in parallel, tried to update their trust policies based on my collected role names.

Trufflehog custom template

GitHub is a good source of AWS role ARNs (the unique identifier of every AWS resource), so after a recommendation from a friend I started using Trufflehog with custom detectors:

Finding AWS Role Arns:

detectors:

- name: AWSRoleNameDetector

keywords:

- AWS

- role

- arn

regex:

awsRoleName: '\b(arn:aws:iam::\d{12}:role/[A-Za-z0-9+=,.@_-]{1,64})\b'

Finding every Arn:

detectors:

- name: AWSResourceDetector

keywords:

- AWS

- role

- arn

regex:

awsResourceName: '\b(arn:(aws|aws-cn|aws-us-gov):[A-Za-z0-9_-]+:[A-Za-z0-9-]*:\d{12}:[A-Za-z0-9+=,.@_-]{1,64}(/.*)?)\b'

BigQuery on Github

The only way to find valid role names is to build a good list, which needs to be tailored to each company. It’s especially hard with IaC, where there’s randomness in naming. Still, it can be useful to collect common role names. I remembered Assetnote’s IIS directory list built with GCP BigQuery, so I tried to find AWS role ARNs from GitHub using BigQuery. I got a list of ~1,500 unique role names and added them to my brute‑force list.

Conclusion

During a year of research I’ve seen both good and bad implementations of AWS connectors. I hope this write‑up helps bug bounty hunters and security teams with cloud integrations in their product. If not, we’re always here to help.